![]()

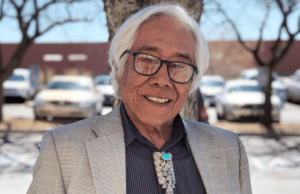

Voices From The Community:

Winning the Lottery in Reverse

by Dave Baldridge

Last year, I unceremoniously collided with the greatest irony of my ongoing 30-year career/mission as an Indian elder advocate. The day before my 74th birthday, the director of a local cognitive assessment center called me into her office to explain her unexpected diagnosis of PSP—progressive nuclear palsy. It’s a terminal neurological disease, loosely related to Parkinson’s or Huntington disease.

Overall, it’s kind of like winning the lottery in reverse—it affects only five out of every 100,000 people. Causes are unknown, but may include genetics . . . although there’s no verified link. It has to do with damaged tau proteins in the brainA primary symptom is frequently the loss of executive function (Ruh Roh!). At the time of the diagnosis, I felt a bit overwhelmed by the irony. IA2 is among the first Native organizations to engage in national work to recognize and cope with ADRD, and then earned the CDC grant that now brings our prestigious Advisory Group together.

Symptoms also include imbalance (I was/am having plenty of that). This has been a long time in the making–a formerly-avid bicyclist, l remember, on a guided mountain bike adventure in Nepal 18 years ago, inexplicably losing my balance and falling off of a steep cliffside trail. There were other incidents.

“Even though it’s progressive,” she explained, “you’ve probably got 8-10 good years left.” So here I sit, a year into this new adventure, internally questioning what “8-10 good years” means.

Will I miss scheduled meetings? Lose my train of thought while presenting at a conference? Break my ankle while walking to the bathroom? Get lost while driving to an appointment? Become wheelchair dependent? Jeez!

The doubts are constant and troubling. They’ve led me to take closer control of my options—re-financing my house, exploring in-home care, should it become necessary, and updating my will and advance directives.

Interestingly, my personal circumstances haven’t seemingly affected my work with ADRD. I’m very appreciative for being able to continue to contribute to our ongoing efforts to help American Indians and Alaska Natives to address ADRD within their communities and families. The issue is top-of-the-ladder for many of my generation and will become even more central as time progresses. Our mission is important.

I’m keenly aware that many of you—my colleagues and friends—have and continue to experience far greater health issues and difficulties than me. I admire your courage and dedication to our work together.

And I’m constantly reminded that many of the folks we serve—Indian elders—face far greater obstacles than I ever have.

I’m convinced that the best solution for me—perhaps for all of us—is actually pretty simple–to stay positive and to keep trying. So, I’ll offer up my best to you, and to Indian elders, as we continue our important work together.![]()

|

![]()

Erin Long, Administration for Community Living (ACL) Office of Supportive and Caregiver Services

Amber Hoon, Tribal Dementia Program Director at Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Council

Part of the reality in Indian Country is that public health approaches to address Alzheimer’s and dementia aren’t always provided by traditional public health entities. One recent example is the Administration for Community Living (ACL) Alzheimer Disease Program Initiative (ADPI) which late last year funded four tribal entities to “provide information and tools to help older adults with dementia and their caregivers anticipate and respond to ties to challenges that typically arise during the course of dementia.” This, one of eight strategies identified in the Road Map for Indian Country (p. 21.).

Tribal ADPI grants awarded in 2020 include:

- Absentee Shawnee Tribe Of Oklahoma (OK)

- Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association, Inc. (AK)

- Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Council (WI)

- Spirit Lake Tribe (ND)

New grantees are required to dedicate a portion of their funds to direct services. By year three, all grantees must devote 45% of grant funding toward direct service programming. Direct services include, but are not limited to, delivery of home and community-based dementia-specific evidence-based and evidence-informed interventions and dementia education and training programs. ACL’s technical assistance center offers a list of programs used in past projects. Additionally, ACL has issued a new funding announcement to support Dementia Capability in Indian Country and applications are due on July 19th.

According to Erin Long from ACL Office of Supportive and Caregiver Services, “A tribally tailored funding announcement made it somewhat easier for tribes with little previous in dementia issues to apply, and we have done the same with this year’s request for proposals.” The Dementia Capability in Indian Country program is intended to support federally recognized tribes, tribal organizations, or consortiums representing federally recognized tribes. Cooperative agreements are for three years for up to $750,000 plus grantees receive significant planning and technical assistance.

Amber Hoon is the Tribal Dementia Program Director at Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Council (GLITC) in Wisconsin, one of the four initial grantees. “We’re early into the work but can see there is a real need and great desire to support persons with dementia in the community, so the themes of this project are getting traction while we are making our work plan final.”

First grants were made seven months ago, and as with everything else, COVID -19 challenges slows progress. “Social isolation has really taken a toll on our Elders, including their thinking skills, which is a new added layer of worry.” She further commented, “when we shift education and support activities to computer-based/online, it comes with challenges of rural access to broadband and extra costs.”

Hoon’s project plan includes training, education, and support for five tribal dementia capability specialists (DCS) and other tribal aging service staff from six tribal partners. Activities include staff training on the Savvy Caregiver for Indian Country curriculum, adaptation of training resources for tribal DCS for cultural relevance, and an outreach and awareness campaign designed to reach a wide range of community agencies and partners. To learn more about the GLITC project, contact Hoon at [email protected].

This E-news is supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of a financial assistance award totaling $348,711 with 95 percent funded by CDC/HHS. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an an endorsement, by CDC/HHS, or the U.S. Government.