-

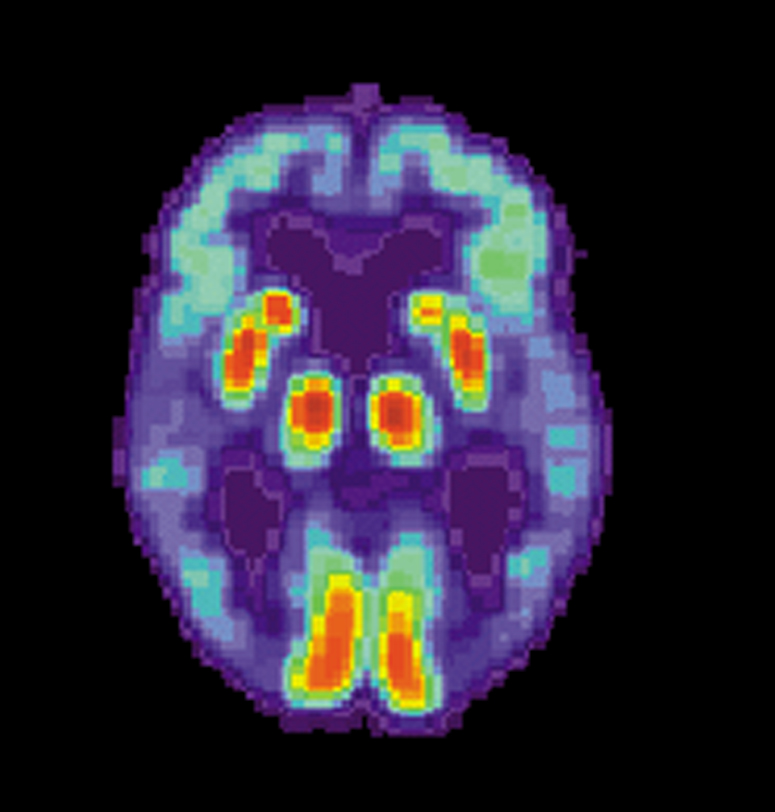

PET scan of the brain of a person with Alzheimer’s disease showing a loss of function in the temporal lobe. (Photo/WikiCommons) BY WESLEY WRIGHT

Dementia affects millions of lives across the United States, and Natives are especially at risk for it given their social context. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, as many as 1 in 3 Native American elders will develop Alzheimer’s or some other form of dementia. Experts say there are a litany of factors that affect how and where Natives receive care for dementia, and medical professionals must be cognizant of them.

History

Like much of the U.S. population, Natives have enjoyed advances in medicine and health care in past decades. Ironically, the longer lives they are now living make them more susceptible to physical and mental ailments that develop in old age.

“Historically, Native people were dying much earlier,” said Dr. Blythe Winchester, a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina. “They weren’t reaching an age where you would expect dementia or other neurodivergent issues, because they weren’t getting old enough.”

Location may also be a factor, since access to medical care is more difficult in some parts of the country. “We know that a lot of us are located in rural districts,” Dr. Winchester said. The federal Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Minority Health estimates that 22 percent of Natives live on reservations or other tribal lands.

Medical providers in rural areas “have often never had the appropriate training” to work with people seeking to manage dementia care, said Jolie Crowder, senior project director for the International Association for Indigenous Aging. A dearth of immediately available resources, she added, means that providers who would like to refer someone to outside care often have a shoddy referral network.

Even as they have lived longer lives on the whole, many Natives have concerns about how physicians will treat them. A special report published in March 2021 by the Chicago-based Alzheimer’s Association found that less than half of Natives surveyed believe they can find a “culturally competent” provider, and almost one-third of Native caregivers reported feeling that providers or staff do not listen to them because of their race.

“They thought they would be treated unfairly,” said Dr. Carl Hill, the association’s chief diversity, equity, and inclusion officer. “Affordability is a factor as well.”

U.S. Census Bureau data from 2018 tallied the poverty rate for Natives at 25.4 percent, the highest among racial minorities in the country.

“Institutional mistrust is a huge factor,” said Jennifer Wolf, the owner and founder of Project Mosaic, a Denver-based consulting company that helped the state of Colorado publicize its plan to address dementia care last year. “They don’t trust outsiders coming into their homes.”

Wolf, who is of Ponca/Ojibwe/Santee ancestry, said that in collecting survey data, she and others repeatedly found that even the idea of bringing in a nurse or caretaker to help aid elder family members is a non-starter for many Natives.

Washington State University nursing professor Ka’imi Sinclair — an unenrolled Western Cherokee — acknowledged that shoddy and unethical research in the past has stifled the gathering of information that would be useful for academics and physicians.

“We’re trying to gather more genetic data, which is difficult because of past research abuses,” she said, noting that there is relatively little historical data on dementia and related mental-health issues among Natives. “It’s been used to stereotype people and all kinds of other things.”

Cultural nuances

Many tribes hold an especially vaunted place for elders, which can complicate matters if older people may need care beyond what they can get at home.

“There is a sociocultural component,” Dr. Hill said. “They really support and hold their elders in high regard, and sometimes that might mean they are more likely to take care of their elders at home.”

Jolie Crowder said the stigma that people might associate with dementia and its symptoms can keep families from addressing it head-on.

“You don’t want your elders to be shamed, because of the high respect for elders in your culture,” she said.

Common medical issues among Natives can exacerbate dementia, Ka’imi Sinclair noted. “We know that diabetes and hypertension, when not controlled, can lead to dementia,” she explained, adding that the federal government has become more willing in recent years to help fund research to detail the ties among them.

Even the symptoms of dementia can be interpreted in different ways, depending on the given context. Where a provider might see symptoms associated with dementia and other neurocognitive issues, some Natives might see a condition to be praised.

“Some tribes actually believe dementia has a connection to life in the spiritual realm,” said Wolf. “Those connections are actually really powerful.”

Dr. Winchester said she’s aware of plenty of times where a provider who isn’t aware of Native contexts may not respond positively or patiently to those with symptoms of dementia, or the ways in which their family members choose to respond.

“We have these things in our culture that for others might seem far-fetched,” she said.

Crowder knows of tribes whose tradition includes never naming diseases, which can greatly complicate the response to any diagnoses. One of her colleagues, an Oklahoma doctor, told her that can prevent them from even discussing dementia.

“We’ve wondered if in some cultures that’s why there is no word for dementia and other related issues,” she said. “Effectively, not naming it may be a way to avoid claiming it, so to speak.”

The encroachment of other cultures into Native life has made some choose to retreat to methods from past generations in some cases.

“I sometimes wonder if we had access to all of those methods, if we would even have as big of an issue,” with dementia and other related disorders, Crowder said.